Self Harm and Suicidal Behaviour

SCOPE OF THIS CHAPTER

Any child or young person, who self-harms or expresses thoughts about this or about suicide, must be taken seriously and appropriate help and intervention should be offered at the earliest point. Any practitioner, who is made aware that a child or young person has self-harmed, or is contemplating this or suicide, should talk with the child or young person without delay.

Note: This chapter must be read alongside the LLR Practice Guidance: Supporting Children and Young People who Self-Harm and/or have Suicidal Thoughts

LOCAL INFORMATION

LLR Practice Guidance: Supporting Children and Young People who Self-Harm and/or have Suicidal Thoughts - This guidance includes links to various resources to further enhance practice and a template for a specific safety plan that can be used to try to create safety for young people and encourages collaboration across agencies to provide solid joined up support.

Self Harm and Suicidal Pathway

Appendix A: Examples of Questions to Ask when Considering the Next Step

AMENDMENT

This chapter was updated throughout in September 2024. Section 3, Risks and Section 4, Protective and Supportive Action must be reread.1. Definition

Definitions from the Mental Health Foundation (2003) are:

- Deliberate self-harm is self-harm without suicidal intent, resulting in non-fatal injury. Self-harm is defined as intentional self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of motive (NICE, 2011);

- Attempted suicide is self-harm with intent to take life, resulting in non-fatal injury;

- Suicidal intent is indicated by evidence of premeditation (such as saving up tablets), taking care to avoid discovery, failing to alert potential helpers, carrying out final acts (such as writing a will) and choosing a violent or aggressive means of deliberate self-harm allowing little chance of survival;

- Suicide is an intentional, self-inflicted, life-threatening act resulting in death from a number of means.

The term self-harm rather than deliberate self-harm is the preferred term as it a more neutral terminology recognising that whilst the act is intentional it is often not within the young person's ability to control it.

Self-harm is a common precursor to suicide and children and young people who deliberately self-harm may kill themselves by accident.

Self-harm is a broad term that can be used to describe the various things that young people do to hurt themselves. It includes cutting or scratching the skin, burning/branding with cigarettes/lighters, scalding, overdose of tablets or other toxins, tying ligatures around the neck, banging limbs/head and hair pulling (Mental Health Foundation, 2006).

The relationship between self-harm and suicidal behaviour is a complicated one. Suicidal behaviour refers to thoughts and behaviours related to suicide and self-harm that don't have a fatal outcome. These thoughts include the more specific outcomes of suicidal ideation (an individual having thoughts about intentionally taking their own life); suicide plan (the formulation of a specific action by a person to end their own life) and suicide attempt (engagement in a potentially self-injurious behaviour in which there is at least some intention of dying as a result of the behaviour).

For the vast majority of young people self-harm is a maladaptive coping strategy intended to help them continue with life not end it. Most self -harm in adolescents inflicts little actual harm, does not come to the attention of medical services and appears to serve an emotional regulation function to manage emotional distress. Self-harm will inevitably reflect an attempt to manage a high level of psychological distress and is usually precipitated by an interpersonal crises and reactive to systemic factors; e.g. being bullied, difficulties at school or work, interpersonal difficulties or relationship breakups, physical or sexual abuse, domestic violence, death of a family member or friend etc. Self-harming behaviour is therefore best understood as a meaning based threat response representing an attempt to cope with the stressors within the individual's life.

Self-harm in primary school aged children is uncommon, with prevalence rates of approx. 0.8%. It is therefore important that particular consideration is given to the possibility of current safeguarding concerns in children of this age group.

2. Indicators

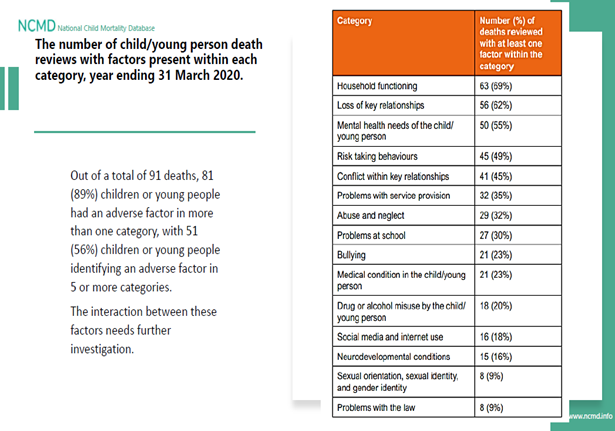

The indicators that a child or young person may be at risk of taking actions to harm themselves or attempt suicide can cover a wide range of life events such as bereavement, bullying at school or a variety of forms of cyber bullying, often via mobile phones, mental health problems including eating disorders, family problems such as domestic violence and abuse or any form of child abuse as well as conflict between the child and parents/carers. See NCMD Report on Suicide in Children and Young People 2021.

The signs of the distress the child may be under can take many forms and can include:

- Cutting behaviours;

- Other forms of self-harm, such as burning, scalding, banging, hair pulling;

- Self-poisoning;

- Not looking after their needs properly emotionally or physically;

- Direct injury such as scratching, cutting, burning, hitting yourself, swallowing or putting things inside;

- Staying in an abusive relationship;

- Taking risks too easily;

- Eating distress (anorexia and bulimia);

- Addiction for example, to alcohol or drugs;

- Low self-esteem and expressions of hopelessness.

3. Risks

An assessment of risk should be undertaken at the earliest stage and should enquire about and consider the child or young person's:

- Level of planning and intent;

- Frequency of thoughts and actions;

- Evidence of or disclosure of substance and/or alcohol misuse;

- Delusional thoughts and behaviours;

- Signs or symptoms of a mental health disorder such as depression or anxiety;

- Self harming behaviours (Note - some types of self-harm are especially dangerous: self-poisoning can be fatal and repeated self-poisoning can cause accumulated organ damage which could be irreversible, ligaturing and the potential for strangulation).

- Low self esteem;

- Social isolation and loneliness;

- Feelings of hopelessness;

- Factors identified as risks by the NCMD as outlined in the infographics above;

- A physical health condition and/or poor physical health that may or may not have a social impact;

- Previous history of self-harm or suicide in parents, carers, siblings, the wider family, or peer group and consideration given to the impact of this and what support can be provided;

- Bereavement whether by suicide or not of a parent, carer, sibling, peer or significant other;

- Consideration given to the impact on the child/young person of parents/carers or family members who have physical health condition or diagnosis, poor physical health or mental health diagnosis/problems;

- Consideration given to the impact on the child/young person of parents/carers where there is substance and/or alcohol misuse;

- Isolated community support;

- Fears of crimes;

- Homelessness or poor housing;

- Difficult times of year or anniversaries;

- Peer issues including friendships, relationship breakdowns;

- Bullying;

- Inadequate provision of basic needs and no access to leisure or social facilities;

- Trauma;

- Academic pressure (especially related to performance and pressure at examination times);

- Poor parental support, relationships, parental separation including divorce and conflict within the family environment;

- Significant pressure placed on the child and setting of unrealistic goals (overachieving or underachieving).

Warning signs:

Children or young people who are self-harming or who are contemplating suicide may display changes in behaviour, for example:

- suicide-related internet use (searching for information about suicide or posting messages with suicidal content);

- physical marks or scarring on the bod;

- expressions of suicidal ideation (especially to peers);

- reluctance to undress or expose specific parts of the body where injuries may be located;

- changes in mood;

- lowering of school grades;

- becoming withdrawn;

- changes in eating or sleeping habits;

- expressing feelings of hopelessness or failure;

- abuse of drugs or alcohol;

- isolation from friends and family.

Any assessment of risks should be talked through with the child or young person and regularly updated as some risks may remain static whilst others may be more dynamic such as sudden changes in circumstances within the family or school setting.

Where a parent or carer is open to adult mental health services, existing processes should include systematic risk assessment of the needs of the child or young person (including thoughts of suicide) by all partner agencies, to ensure they receive appropriate support.

All schools across LLR (including private schools) should include links/references to guidance on assessing the risk of suicide for children & young people experiencing bullying within their behaviour/anti-bullying policies.

All schools across LLR (including private schools) should consider multiagency involvement for children & young people at risk of Exclusion.

Where children or young people have been suspended or permanently excluded, schools should add signposting to universal health (physical &mental health) services within Local Authority letter templates for letters to send to their families.

See LLR Practice Guidance on Bullying.

The focus of the assessment should be on the child or young person's needs, and how to support their immediate and long term psychological and physical safety.

The level of risk may fluctuate and a point of contact with a backup should be agreed to allow the child or young person to make contact if they need to.

The research indicates that many children and young people have expressed their thoughts prior to taking action but the signs have not been recognised by those around them or have not been taken seriously. In many cases the means to self-harm may be easily accessible such as medication or drugs in the immediate environment and this may increase the risk for impulsive actions. A plan for safe storage of medication in the household and other potential items which may be used by young people to self-harm should be made with all at risk young people and their parents/carers. GP's should be aware of risk of self-harm when prescribing medication for the young people who self-harm and their family. Whilst no medication is safe taken in this context, certain medication may pose a much greater risk of harm, or death, and this should be considered when prescribing to at risk young people and others in the household.

If the young person is caring for a child or pregnant the welfare of the child or unborn baby should also be considered in the assessment.

4. Protective and Supportive Action

A supportive response demonstrating respect and understanding of the child or young person, along with a non-judgmental stance, are of prime importance. Note also that a child or young person who has a learning disability may find it more difficult to express their thoughts.

Practitioners should talk to the child or young person and establish:

- If they have taken any substances or injured themselves, if so, the severity of this and whether medical treatment is needed;

- Find out if there is an immediate concern for the child or young person's safety;

- The location of the child or young person;

- Find out who they are with – if anyone;

- Find out what is troubling them;

- Explore how imminent or likely self-harm might be;

- Find out what help or support the child or young person would wish to have;

- Find out who else may be aware of their feelings;

- Find out what they would like to happen - their hopes and expectations.

And explore the following in a private environment, not in the presence of other pupils or patients depending on the setting:

- How long have they felt like this?

- Are they at risk of harm from others?

- Are they worried about something?

- Ask about the young person's health and any other problems such as relationship difficulties, abuse and sexual orientation issues?

- What other risk taking behaviour have they been involved in?

- What have they been doing that helps?

- What are they doing that stops the self-harming behaviour from getting worse?

- What can be done in school or at home to help them with this?

- How are they feeling generally at the moment?

- What needs to happen for them to feel better?

Do not:

- Panic or try quick solutions;

- Dismiss what the child or young person says;

- Believe that a young person who has threatened to harm themselves in the past will not carry it out in the future;

- Disempower the child or young person;

- Ignore or dismiss the feelings or behaviour;

- See it as attention seeking or manipulative;

- Trust appearances, as many children and young people learn to cover up their distress;

- Feel that you need to manage this alone, seek support, advice and guidance as required. (if you need to gain further information or support, advise the young person of the timeframe for when you will be in touch again and agree the preferred contact details).

Referral to Children's Social Care:

The responses and information provided by the child or young person/parent/carer or information shared by services will inform whether the child/family require support under early help offer or whether a social work assessment is required and/or support needed from specialist services such as CAMHS or Harmless.

Practitioners should take a holistic approach and be mindful that not every case will require the same level of intervention.

Where there are low level concerns about self-harm and suicide these may be able to be addressed with the support of friends and family or other services such as the GP, School Nurse, school counsellors, on-line counselling, or early intervention services such as Relate or Mental Health support Teams in schools. If concerns are not decreasing/needs being met by these services, a referral to more specialist support such as CAMHS should always be made, and consideration given to a referral to Children's Social Care.

The child or young person may be likely to suffer significant harm, which requires child protection services under s47 of the Children Act 1989, may be a Child in Need of services (s17 of the Children Act 1989), or may require an early help assessment a referral to Children's Social Care should be considered.

Practitioners should consult their local Thresholds guidance to establish what level of intervention is required and seek advice from their designated Safeguarding Lead. If there is still uncertainty, practitioners should contact children's social care for advice.

Advice can be sought from the Duty Social Work Teams below:

Leicester City CSC

Telephone: 0116 454 1004

Email: casp-team@leicester.gov.uk

Leicestershire CSC

Telephone: 0116 305 0005

Leicestershire use a MARF: Multi-Agency Referral Form for Early Help and Social Care services

Rutland CSC

Telephone: 01572722577

Email: dutyteam@rutland.gov.uk

Harmless

Professionals should consider referring to Harmless. Harmless is the national centre of excellence for self-harm and suicide prevention. Their work is based on promoting health and recovery, reducing isolation and distress, and increasing awareness and skill in intervention. Harmless work with children and families to provide support.

Further information is available here: Professionals - Harmless

Referrals can be made: Referral Form Leicester and Rutland - Harmless

CAMHS

Professionals can consider a referral to CAMHS. There are different services within CAMHS that can be utilised for support.

CAMHS is a specialist service offering mental health assessment and intervention to children and young people up to 18 years who need more specialist support with their mental health, and this includes self-harm and suicide.

Where there are serious concerns and an urgent mental health response is required, a referral can be made to the Crisis Resolution and Home Treatment team which provides rapid assessment and management for child and young people with a mental health crisis (including self-harm and suicide or any other escalating risk where without intervention, hospital admission or health related residential placement would be required).

The service operates 365 days per year between 8am and 10pm seven days a week.

Outside of this time Practitioners can access telephone support via CAP on 0808 8003302.

Out of hours urgent assessments can be conducted at the Bradgate Unit Hub or by the All-Age Mental Health Triage and Liaison Team based at LRI supported by the CAMHS On Call Once a referral is made, a response should be received within 2 hours and an assessment completed within 24 hours.

If early help or low intervention is not decreasing risks or concerns are increasing, specialist support should always be sought and consideration given to a referral to Childrens Social Care.

Where hospital care is needed:

Where a child or young person requires hospital treatment in relation to physical self-harm, practice should be in line with the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) June 2013 (see NICE website):

Those children who attend University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust ("UHL") will be assessed for their clinical need and managed within the hospital accordingly. All children who attend UHL will have a mental health assessment prior to their discharge. A plan for any mental health follow up will be put in place by the assessing mental health team prior to the child leaving hospital.

5. Issues – Information Sharing and Consent

The best assessment of the child or young person's needs and the risks, they may be exposed to, requires useful information to be gathered in order to analyse and plan the support services. In order to share and access information from the relevant professionals the child or young person's consent will be needed.

Professional judgement must be exercised to determine whether a child or young person in a particular situation is competent to consent or to refuse consent to sharing information. Consideration should include the child's chronological age, mental and emotional maturity, intelligence, vulnerability and comprehension of the issues. A child at serious risk of self-harm may lack emotional understanding and comprehension and the Gillick Competence should be used. Advice should be sought from a Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist if use of the mental health act may be necessary to keep the young person safe.

Informed consent to share information should be sought if the child or young person is competent unless:

- The situation is urgent and delaying in order to seek consent may result in serious harm to the young person;

- Seeking consent is likely to cause serious harm to someone or prejudice the prevention or detection of serious crime.

If consent to information sharing is refused, or can/should not be sought, information should still be shared in the following circumstances:

- There is reason to believe that not sharing information is likely to result in serious harm to the young person or someone else or is likely to prejudice the prevention or detection of serious crime; and

- The risk is sufficiently great to outweigh the harm or the prejudice to anyone which may be caused by the sharing; and

- There is a pressing need to share the information.

Professionals should keep parents/carers informed and involve them in the information sharing decision even if a child is competent or over 16. However, if a competent child wants to limit the information given to their parents or does not want them to know it at all; the child's wishes should be respected, unless the conditions for sharing without consent apply.

Where a child is not competent, a parent/carer with parental responsibility should give consent unless the circumstances for sharing without consent apply.

It is best practice for children/young people/families to receive support from agencies within their local area where possible. This is applicable to health, education, social care and wider support services that maybe on offer.

Where a child/young person/family is known to services or receiving support or is identified as self harming/risks of suicide and at any stage in the process of working with or starting work with them, the parents/carers and/or the child move from one household to another (this includes planned or unplanned or temporary moves) to a different local authority, professionals should consider and know what to do when this happens.

The effective co-ordination and robust transfer of information to local agencies is critical to safeguard and promote the welfare of children.

Cross Boundary Referrals

If a school or professional is making a referral for services for example first response or a MARF, do not assume the referral is to the local authority where the school is geographically located. Prior to referral the referrer needs to first check the local authority for the address where the child lives to ensure the referral goes to the correct authority.

The address and post code can be checked here.

For more information, see Children and Families Moving Across Local Authority Boundaries Procedure.

Further Information

These links relate to publications about self-harm and suicide with sections about children and young people as in the latest national strategy:

The Truth About Self-harm, The Mental Health Foundation

Suicide Prevention: Resources and Guidance, GOV.UK

Suicide by Children and Young People 2017, (HQIP)

Self-harm: Assessment, Management and Preventing Recurrence NICE Guidance

Help Lines and Websites, including Local Resources:

| Support for your mental health and overall wellbeing (LLR ICB) | Information for parents, carers and professionals on the support that's available for young people across Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland. |

| Including 'No harm done' | Mental health information & leaflets for young people & parents/carers |

| 0800 068 4141 | Organisation that supports the prevention of young suicide including helpline (Hopeline UK) |

| 0800 1111 | Emotional health advice & counselling |

| Calm Harm | Mobile App for Children & Young People |

| Anna Freud – National Centre for Children & Families | Emotional & Mental health resources for children, families & schools including leaflets and podcasts |

| Joy | Helps people find activities, support and groups near them. |

| MIND | Emotional health & mental health information & information leaflets |

Samaritans 08457 909090 |

Telephone counselling/crisis support |

| Grass Roots | Grass Roots - suicide prevention Downloadable resources |

| Harmless | Service user led resource including online information & support to those who self-harm and carers/family |

| National Self Harm Network | Self-harm information leaflets and forum |

| Mental health - NHS | Practical information, interactive tools & videos |

| Northumberland Tyne and Wear NHS Trust | Service user leaflets and self-help guides on a range of mental health difficulties |

Information page and self-help for self-harm |

|

NHS.UK NHS Apps Library |

Mental health & wellbeing information, crisis support & self-help apps |

Chat Health Leicester: 07520 615 381 Leicestershire & Rutland: 07520 615 382 |

Text messaging service for health advice for parents/carers |

| NSPCC | Information for parents/carers on supporting a young person who self-harms |

| Tellmi | Free, safe & anonymous online support for young people |

|

Leicester text: 07520 615 386 Leicestershire & Rutland text: 07520 615 387(Available weekdays 9am – 5pm) |

Confidential text messaging service that enables children and young people (aged 11-19) to contact their local public health nursing team. |

| Health for Teens | Health promotion website with local links and resources |

| Health for Kids | Health promotion website with local links and resources aimed at younger children (approx. primary school age) |

| Freephone 0808 808 4994 | Emotional health advice for under 25s |

| Kidscape | Resources on bullying, including cyberbullying, transition to secondary school & sexual abuse |

| 0808 2000 247 | Domestic Violence Helpline |